Social media has always fascinated me. As it continues to grow and dominate much of Western society, I have always been interested in how society, the law and technological or communication developments are going to negotiate the increasingly complex mediascapes of the 21stcentury. With my pre-existing interests, beliefs and knowledge around this area of study in my own cultural setting, I am considering looking into China’s use of social media and the government intervention over such use. Online censorship in China is the responsibility of Internet content providers. Each individual site privately employs up to 1000 censors in attempts to avoid paying fines or being shut down if they don’t comply with the governments censorship guidelines as well as enforcement from hundreds of thousands of ‘internet police’ (wang jing) and internet monitors (wang guanban) (King, Pan & Roberts 2013, p. 326).

Before reading any further, Michael Anti, Chinese blogger’s TEDtalk, ‘Behind the Great Firewall of China’, usefully breaks down the differences, limitations and developments of the Internet v. the ‘ChinaNet’. Anti draws on his own experiences as a blogger in China’s national public sphere. If you are not up for the whole 18 minute’s, a shorter video follows with a similarly useful breakdown of China’s internet use.

For the lazy (or time constrained) ones…

Through an analytic auto-ethnographic research approach, I will engage with secondary sources relating to Internet and social media use in China, while simultaneously narrating my own experience with Weibo or Renren (or potentially both, depending how difficult they are to navigate). Weibo is considered the Twitter of China and Renren, the Facebook.

Through my own interaction and experiences of the platform(s), I will explore and (hopefully) achieve what Leon Anderson (2006) determines to be the key elements of analytical auto-ethnography in his article, Analytical Autoethnography. Anderson identifies five elements, (1) complete member researcher status, (2) analytical reflexivity, (3) narrative visibility of the researcher’s self, (4) dialogue with informants beyond the self, and (5) commitment to theoretical analysis (Anderson 2006, p. 378).

While I of course am not in China, this experience will be slightly altered. Additionally, I am not going to be as connected to other users (in that I do not know anyone else that users Weibo, at least to my knowledge) thus will not have the same experience as Chinese users, affecting my ability to approximate the emotional stance of the people I am studying (Anderson 2006, p. 380). This will essentially inhibit the facilitation of myself being of a complete member researcher status, the first key element of analytical auto-ethnography. However, creating my own Weibo or Renren account is as close as I will get to being a full member in the research setting and by recognising this limitation I have essentially engaged in the second key element identified by Anderson, analytic reflexivity.

Through live tweeting my experiences of the Weibo or Renren platform on twitter and hopefully Weibo/Renen (depending how good my skills are) and documenting my research into China’s government control over its use, I am making myself a visible and active researcher in the text, which is identified by Anderson as the third key element of analytical autoethnography. As noted, I will attempt to make connections with other users of Weibo/Renren, while acknowledging that this may be limited and difficult given I do not speak Chinese or know any one that uses Weibo, so my ability to achieve Anderson’s fourth element of analytical autoethnography may be my weakest. This will become apparent once I create my Weibo account and attempt to navigate my way through it and the accounts of others. Finally, my commitment to theoretical analysis, the fifth element Anderson identifies, will come through my engagement in secondary source analysis in conjunction with my reflexive approach while engaging and documenting my own experiences of the research.

Upon first Googling ‘Weibo’, I was met with Safari couldn’t find this page. What I initially thought was that I have encountered my first roadblock, that being that I am not in China so cannot access Weibo. I was, however, pleasantly mistaken. Upon reloading the page I got through. But then of course, I was met with my first real roadblock. The language barrier. Of course, being a Chinese platform everything is in Chinese.

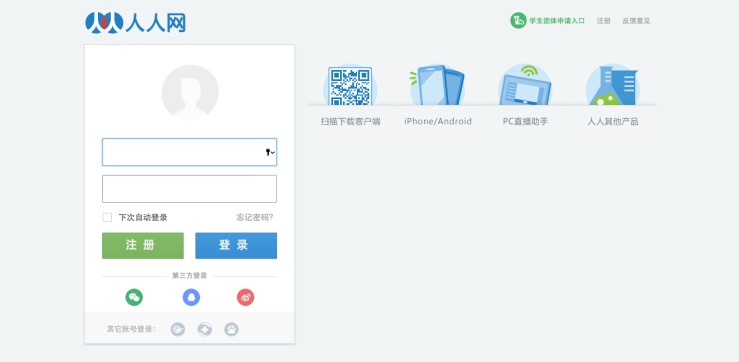

This was of course the same upon Googling ‘Renren’…

So it was then, that I realised I would have to use Google translate to disseminate what it was that I was actually reading and signing up for essentially. While of course this complicated my interaction with the platform, it also excited me. It meant I could document my interaction with the platform and my use of Google translate with the platform, to add another layer and element to include in my digital artefact. Through using Google translate online while directly accessing Weibo, I was unsuccessful in getting a translation, but may have luck with the app on my phone.

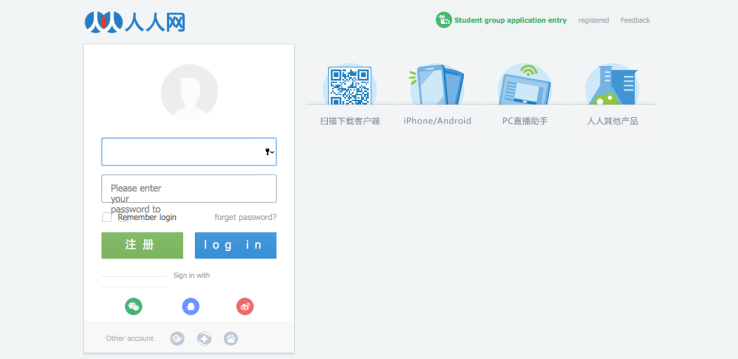

I did have more luck with Renren…

This may mean that I use Renren to narrate my own experience. At the moment, I think I will present my project through a Prezi or a blog post to provide for a more interactive and engaging method of communicating an analysis of my experiences and research. I will embed the Prezi or the post with both my live tweets, pictures and videos of my use of Google translate.

References:

Anderson, L 2006, ‘Analytic Autoethography’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, vol. 35, no. 4

King, G, Pan, J & Roberts, M 2013, ‘How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression’, American Political Science Review, vol. 107, no. 2

Social Media Censorship in China: how is it different to the West?, BBC Tech, weblog post, 26 September 2017, viewed 7 September 2018, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsbeat/article/41398423/social-media-and-censorship-in-china-how-is-it-different-to-the-west>

TED 2012, Michael Anti: Behind the Great Firewall of China, online video, 30 July, viewed 7 September 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yrcaHGqTqHk>

The New York Times 2016, How China Is Changing Your Internet, online video, 9 August, The New York Times, viewed 7 September 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=80&v=VAesMQ6VtK8>

Reblogged this on Digital Asia.

LikeLike